Referendum, Benedetta Tobagi: "Un voto contro i depistaggi, per la verità"

3 maggio 2024

One was 45 years old, from Gela, and claimed innocence. The other asked to serve his sentence in his motherland, Russia. The former did not eat for 41 days, the latter for 61. Both were held in the Augusta prison and were not heard. Both died after a long hunger strike. Ignored by the media.

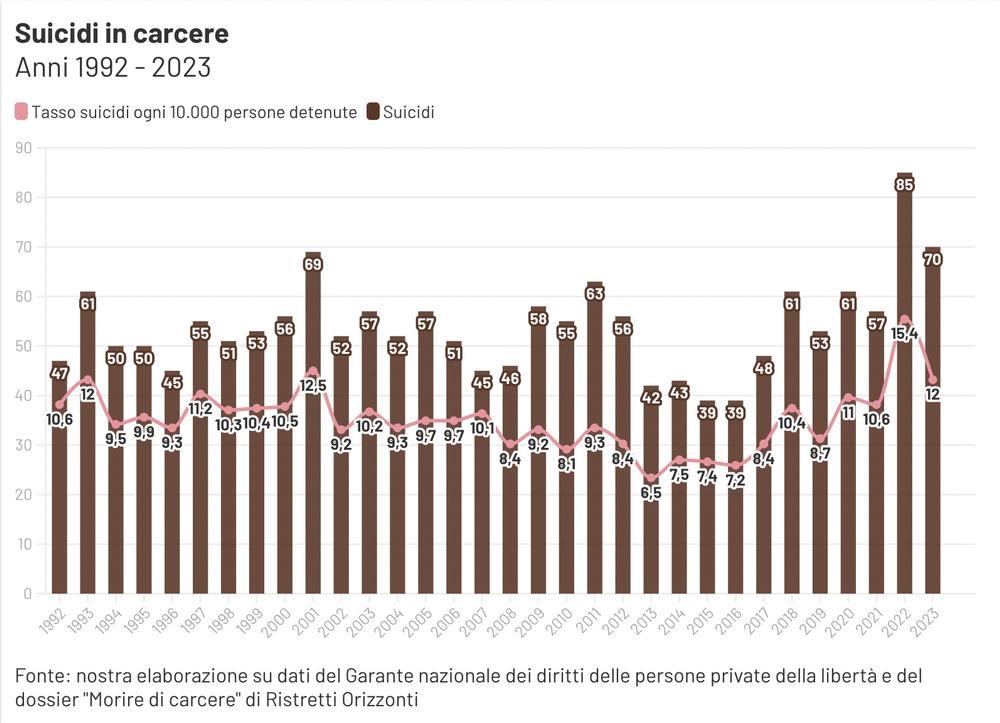

These are two of the stories collected in the annual report of Antigone, the prisoners' rights association, now in its 20th edition (Nodo alla gola). This time the focus is the continuing suicide emergency in penal institutions. After 2022, a record year with 85 ascertained suicides, 2023 continued to record unprecedented numbers: 70 people decided to take their own lives in Italian prisons. A figure approached only once in the last thirty years: in 2001, with 69 deaths.

But it is above all the trend at the beginning of 2024 that is worrying: between the beginning of January and mid-April, 30 people killed themselves in prison institutions. One every three and a half days. While in 2022, in mid-April, there were 20. 'If the pace were to continue in this way,' specifies the Antigone association, 'at the end of the year we would risk reaching even more dramatic levels than those of the last two years'.

Meanwhile, today an operation led to the arrest of 13 prison police officers, and the suspension of eight others, for alleged torture and violence inflicted on under-18s held in Milan's Beccaria juvenile prison.

Interpol warns: "Cybercrime will be easier with artificial intelligence"

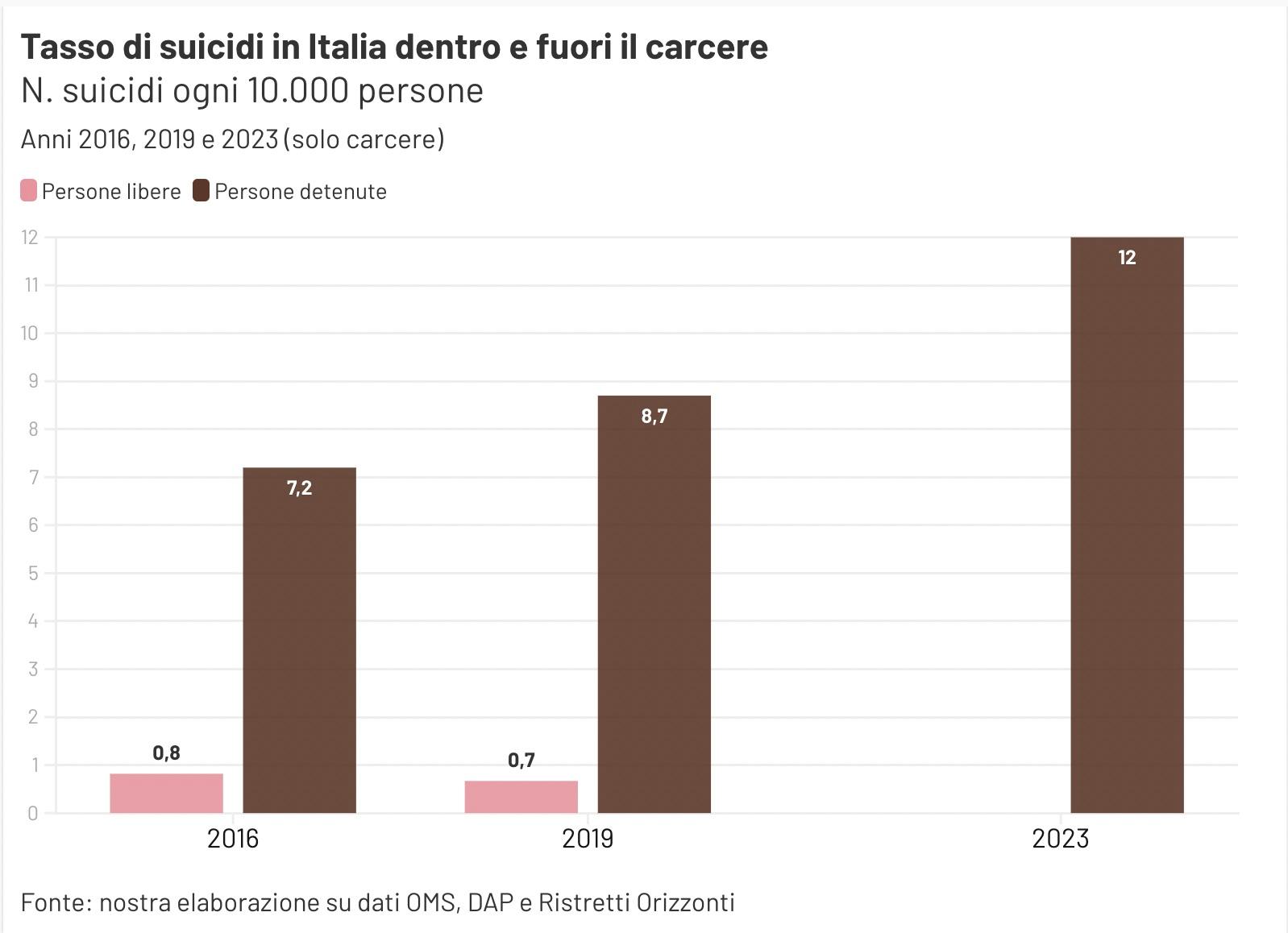

An important indicator of the extent of the phenomenon is the so-called suicide rate, i.e. the relationship between the number of deaths and the average number of persons imprisoned during the year. In 2023 it amounted to 12 cases per 10,000 persons, recording - after 2022 - the highest value in the last twenty years. This value even looks set to rise in 2024.

Further proof of the structural nature of the problem is the comparison with what happens outside penal institutions. According to the latest data published by the World Health Organisation (WHO), the suicide rate in Italy in 2019 was 0.67 cases per 10,000 people. In the same year, but in prison, the figure was 8.7 per 10,000 inmates. This means that 18 times more people take their own lives in a cell than outside.

Not only that. While at the European level, Italy is considered a country with a low suicide rate, it is above the EU average for voluntary deaths in prison. According to the latest data from the Council of Europe, dating back to 2021, in our country the suicide rate in penal institutions is 10.6 cases per 10,000 people, while the European average is 9.4.

Of the 100 people who took their own lives in prison between 2023 and 2024, five were women. In percentage terms, the incidence is higher than for men, but not only that: it is also a particularly high number if we consider that the female prisoner population only accounts for 4.3 per cent of the total. In particular, in the summer of 2023, three women took their own lives inside the female section of the Turin prison.

The first was 52 years old and of Romanian origin. She had almost finished serving her sentence and was due to be released within two months. Also in Turin, on 9 August, S. J., a 42-year-old Nigerian woman, died. She had been in a cell since 21 July, after a long period under house arrest. Since entering prison, she had stopped drinking and eating, refusing any kind of treatment. Her only request was to see her children and husband. After 18 days of detention, she allowed herself to die of hunger and thirst. A few hours later, in the same section, A. C., a 28-year-old girl from Liguria. She had been in prison for about three months for a conviction that came in April for an accumulation of offenses, mainly petty theft. Many dated back to 2013 and 2014 and were linked to her drug addiction problems.

Looking at nationalities, it emerges that the incidence of voluntary deaths is higher among people of foreign origin (28 suicides for an average inmate population of 18,185), with a rate of 15 cases per 10,000 people, compared to 10.5 among Italians.

As regards age: the average age is 40. The most represented age group is between 30 and 39, with 33 cases of suicide. This is followed by those between 40 and 49, with 27 episodes. Then there are the youngest, with 17 suicides committed by boys and girls aged between 20 and 29. In addition to biographical data, the media give information on the pathologies suffered. Antigone specifies: 'This is a delicate terrain, in which, in the absence of more verification tools, the use of the conditional is a must'. But from the data available, at least 22 of the 100 people who died suffered from psychiatric pathologies. At least 12 had already tried to take their own lives on other occasions, while seven had a history of drug addiction. At least six were homeless.

The Eureka investigation reveals the borderless business of the 'ndrangheta

One of the main problems in prison remains the presence of widespread psychic distress: 12 per cent of prisoners have a serious psychiatric diagnosis. And the massive use of psychotropic drugs remains the main tool for treating mental health in cells: 20 percent of inmates regularly use mood stabilizers, antipsychotics and antidepressants. Forty per cent use sedatives or hypnotics. Conversely, a course of treatment is almost non-existent. In 2023, an average of 100 prisoners had ten hours per week for psychiatrists and 20 hours per week for psychologists. While the mental health protection units, mainly health-care-managed sections, are today concentrated in a few institutes. In our country, there are 34 active ones in 32 penitentiary institutes (out of 190 total prisons) and they accommodate about 300 people.

In 2023, Antigone recorded 122 compulsory health treatments (Tso) carried out in prison: an illegal practice if carried out within the prison sections without admitting the person to a hospital (Psychiatric Diagnostic and Treatment Service - Spdc), as required by law.

Another alarming issue recorded by the association is that inmates with mental distress or mental disabilities are increasingly subjected to solitary confinement, which can be used for disciplinary, health or judicial reasons. For example, a visit to the Santa Maria Capua Vetere prison revealed that some of those in solitary confinement had psychiatric diagnoses, even serious ones. In general, 'solitary confinement hurts and is used too much', points out the Antigone observatory, adding that in 2023, disciplinary solitary confinement was used especially in institutions where more than half of the population was foreign.

Another issue is the waiting lists to enter the Residences for the Execution of Security Measures (Rems), to which people declared socially dangerous and (in whole or in part) incapable of understanding and wanting when they committed the crime, the so-called insane offenders, should be destined. The Rems since 2014 have progressively replaced the judicial psychiatric hospitals. But the long waiting lists - in the opinion of the Constitutional Court, which in 2022 called for an overall reform of the system - do not guarantee "either the effective protection of the fundamental rights of potential victims of aggression, which the person suffering from mental pathologies could again realize" or "the right to health of the sick person, to whom while waiting, the treatments that should instead be assured to him are not practiced".

At the end of January 2024 755 people were waiting to enter Rems, 45 of them waiting in prison, in many cases without a valid detention order. This is not an unusual procedure. In 2023, one out of every five guests, before entering Rems, had spent a period in prison: routes that are not in line with regulations and potentially harmful to health. According to the association, however, the solution is not to build more facilities. A measure, it says, 'not very justifiable from a therapeutic point of view and not sustainable at all from an economic point of view, which would risk betraying the reform of the closure of the judicial psychiatric hospitals'. The crux of the matter is to avoid that the Rems are occupied by people who could take advantage of alternative measures, such as being sent to the community.

On 31 March 2024, there were 61,049 detained persons, against an official capacity of 51,178 places, from which, however, the unavailable places must be subtracted: 3,640. This is a number that changes over time, but the Ministry's 2023 Report on the Administration of Justice shows that it tends towards a 'physiological threshold of five percent' at best. At least 2,500 fewer prison places at any given time are, therefore, inevitable.

On the other hand, admissions continue to grow, and in the last year even more strongly. From the end of 2019 to the end of 2020, due to the deflationary measures taken during the pandemic, prison admissions had dropped by 7,405. But they immediately rose again. First slowly, with an increase in admissions of 770 in 2021, which was then followed by a growth of 2,062 in 2022 and even 3,970 in 2023. In the last year, therefore, the growth in admissions averaged 331 units per month, an alarming growth rate, which if confirmed in 2024 would take us over 65,000 people by the end of the year.

A growth that is linked to a crackdown on the political and legislative front. The season of new offenses and penalty increases began with the so-called "rave decree", continued with the "Caivano decree", then with the "Security bill", the latter still being examined by Parliament, which punishes possession of material for the purpose of terrorism (2 to 6 years), arbitrary occupation of property used as someone else's home (2 to 7 years), amending Article 600-octies of the Criminal Code by inserting inducement and coercion to begging (penalty 2 to 6 years), Article 583-quater of the Penal Code is amended again to punish those who cause bodily harm to a police officer or agent (from 2 to 5 years) and the offense of rioting in a penal institution is introduced (from 2 to 8 years).

Antigone's data in hand, the effects of the Caivano decree were immediate. At the beginning of 2024, there were about 500 young people detained in Italian penal institutes for minors (Ipm). A similar figure had not been reached for over ten years.

Antigone's report concludes with four proposals to improve the situation.

Alternative paths for those with psychiatric and addiction problems. In addition to favoring alternative paths to intramural detention, especially for those with psychiatric and addiction problems, it is necessary to improve life inside institutions, to reduce as much as possible the sense of isolation and marginalization. There is a need to ensure greater availability of activities, be they work, training, or cultural.

More contact between inside and outside prison. More openness in relations with the outside. It is not enough to increase the monthly telephone calls (of 10 minutes each) from 4 to 6. Phone calls should be liberalized. The Constitutional Court ruling on the right to affectivity should be followed up by providing places in prisons where intimate talks are possible.

Ad hoc wards and psychological courses for those entering or leaving prison. The beginning and end of a prison term are very delicate phases. The introduction to prison life should be gradual and each prison should have ad hoc wards for so-called new arrivals. Likewise, resources should be invested in the preparation phase for release. The person should be accompanied back to society and provided with the main necessary tools. A release preparation service would be needed, in connection with external territorial bodies and services.

This article was published by our partner Kompreno translated with the support of DeepL.

La tua donazione ci servirà a mantenere il sito accessibile a tutti

Riformata. Così il governo vorrebbe la magistratura, ma l'obiettivo è solo limitarne il potere

La tua donazione ci servirà a mantenere il sito accessibile a tutti