Milano-Cortina. Ecco come verranno spesi i 450 milioni di euro delle paralimpiadi

4 aprile 2024

In 2024, as many as 76 countries around the world are called to the polls to elect their representatives, and almost a quarter of these nations are on the African continent, which meanwhile is at the centre of a profound transformation. After years of exploitation, Africa is increasingly claiming autonomy from European and Western influence. Many countries have shown that they want to emerge internationally, for example through the African Union's attempts to mediate in the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. The continent wants to increasingly distance itself from the role of a passive market, where it buys raw materials cheaply, to become a strategic gaming table at which not only the hosts but also the world's major players sit. However, it must keep at bay the interests of China, Russia and Turkey, which are aiming to grab its rich natural resources, and more.

On paper, the vote could be the key to opening a new chapter, but history teaches us that every electoral round in Africa is complicated by the major critical issues that affect most of its states. The risk, as has happened in the past, is that the appointment at the ballot box will turn into a plebiscitary referendum, aimed at keeping the powerful man in power firmly in government. On many occasions, it has already happened, citizens have voted in the midst of war or have been denied the right to express a preference because they have been forced into refugee camps far from their homes. Add to this foreign interference, which could slow down or block the process of slow awareness that is underway and widespread, especially among the younger generations. Certainly these elections will produce important geopolitical consequences.

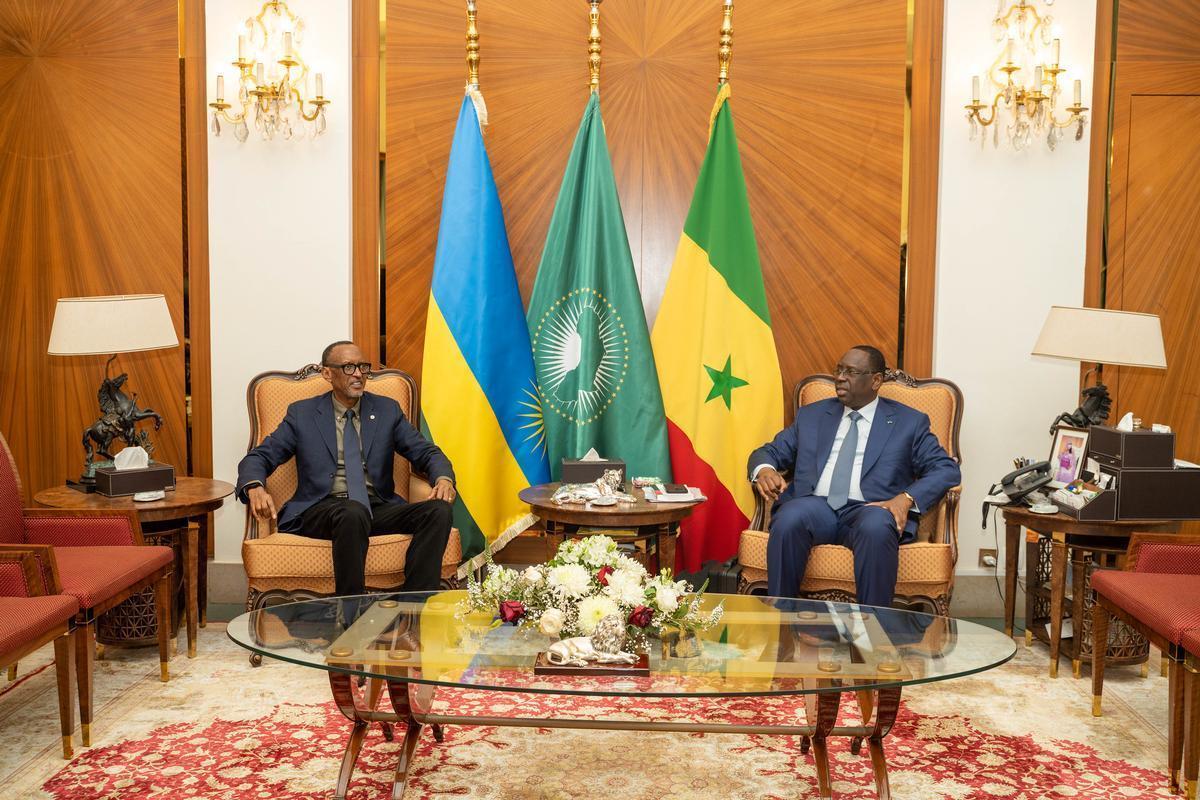

Senegal, a key country for West Africa, has chosen the turning point. In the past, thanks to its stability, it has often played the role of mediator in events concerning neighbouring countries. The presidential elections, held on 24 March after a troubled path, saw Bassirou Diomaye Faye, the opposition candidate, triumph with 54% of the vote against the challenger Amadou Ba, a member of the party currently in government. The youngest president in the country's history, Diomaye Faye thus takes the place of Macky Sall, former leader of the African Union, a loyalist of Paris, in office since 2012. France maintains very solid relations with Dakar and seems to have entrenched itself in the country after having watched almost impotently as the now former Françafrique, a term describing relations between France and the former African colonies after their independence, crumbled.

Senegal, however, is also struggling with a difficult economic situation and the younger fringe of the population has taken to the streets several times to protest against the government. After giving up running for a third term, which is not provided for in the Constitution, Macky Sall had postponed the elections, while the judiciary had invalidated the candidature of the opposition strongman, the questionable Ousmane Sonko. A champion of qualunquism, with a predilection for radical Islam and homophobic and sexist positions, but adept at intercepting popular discontent, especially among the young. In the following months, his loyalists had put the main cities of the state to the sword to protest against his conviction and he had declared war on France and Europe, saying he was ready to throw Senegal into the arms of the Chinese dragon. Unable to run, it was Sonko who launched the candidacy of Diomaye Faye, who rewarded him by appointing him prime minister: a choice that could lead Beijing to dominate the Senegalese economy.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, on the other hand, continuity triumphs: last December, the country re-elected President Felix Tshisekedi with an overwhelming majority. It is a pity that five million Congolese were unable to vote because they fled their homes, while the inhabitants of the eastern provinces of the country did not even have seats, given the extreme instability of the region prey to militias that rob, rape and massacre the locals.

Foreign influences have also been decisive in the states of the Sahel belt, where an endless series of coups have taken place over the past three years. Mali, led by a military junta, recently held a constitutional referendum that was massively attended by the population and gave enormous powers to the head of state. On an as yet unspecified date, a vote is due to be held in which Colonel Assimi Goita, head of the military junta, has already declared his intention to participate. For the man 'invented' and supported by the Wagner Group - which is doing gold business in the very poor African country thanks to the exploitation of gold mines - victory is not in question. Also in the hands of the military and Moscow is Guinea, which through the mouth of its strongman, Colonel Mamady Doumbouya, has repeatedly declared the urgency of a diplomatic transition for the country. The fact remains that in 2024 the only elections planned are a sort of referendum on the approval of the military junta that holds power in Conakry.

More complex instead is the situation in Chad, the last state still hosting French bases in Central Africa. Here, control has passed with a white coup (i.e. without victims) from father to son and the scion Mahamat Idriss Deby has inherited absolute power from the old 'gendarme of Paris'. In N'Djamena, the capital, the government is half-civilian and half-military, but Deby has repeatedly stated that he wishes to have maximum popular support. He could therefore stick to the election date of next October, even though there will be no opponent to contest him for victory. And those who do not vote for him risk paying dearly.

Those just mentioned are three examples of elections far removed from what we understand as the exercise of democracy, in states that are nevertheless crucial for the stability of a complicated area such as the Sahel. Even more complex, if possible, is the situation in Somalia, which has scheduled elections in June 2024.

In Mogadishu, a small revolution in voting methods is expected, because for the first time direct universal suffrage will be introduced. A real election has not been held in the Horn of Africa country since 1969, with the system having always given a lot of power to the clans, which determine the composition of the parliamentary assembly. The application of the 'one person, one vote' system was strongly desired by the current government, but for the moment its real power only extends to the capital and the central provinces. The north and west of Somalia, in fact, are still in the hands of the al-Shaabab, Islamic extremists affiliated with al-Qaeda, who want to turn the country into an Islamic emirate: a genuine anti-State that the government is unable to contain.

Among other things, the vote will not affect the province of Somaliland, the former British Somalia, which has been self-proclaimed independent for over 30 years and is still seeking international recognition. It is precisely this territory that is at the centre of a heated diplomatic clash between Ethiopia and Somalia, because Addis Ababa is looking for an outlet to the sea and Somaliland has allegedly come forward by offering the port of Berbera. Mogadishu immediately objected, explaining that Somaliland cannot freely dispose of Somali territory and that this move by Ethiopia would lead to international recognition of a self-declared state.

Within the sensitive Great Lakes region, tiny Rwanda, which despite its size is a geopolitical giant, will also go to the polls in 2024. The Rwandans have a decisive weight in the balance of Congo, which borders Kigali: they arm and train fierce militias that plunder Congolese mines and terrorise the local population. All this under the control of President Paul Kagame, re-elected unimpeded since 2000 after six years as vice-president and a military victory against the Hutu, the Rwandan ethnic group responsible for the 1994 genocide.

The presidential and parliamentary elections will be held next 15 July and there are unlikely to be any surprises. In the last elections, in fact, Kagame obtained 98.63% of the vote and was re-elected for another seven years in 2017: an electoral farce, with the opposition annihilated and forced to flee. Among Kagame's biggest opponents is Paul Rusesabagina, the man who saved more than a thousand Tutsis during the genocide (inspiring the screenplay for the film Hotel Rwanda) and who was sentenced to 25 years in prison on terrorism charges for criticising the president. The country is ranked as the second worst in the world for freedom of speech, behind only Eritrea, and these elections will turn into yet another catwalk for Kagame.

The presidential elections to be held in August in South Africa, the leading economic power on the African continent, deserve special attention. Since 1994, the African National Congress, Nelson Mandela's party, has reigned in Pretoria, but this time victory seems less certain. The party has been hit by a series of financial scandals involving some of its top leaders, including the current president Cyril Ramaphosa.

Moreover, the country is going through a serious crisis, with a very high unemployment rate and an economy in extreme difficulty, which has even fallen below its 2008 level. Ramaphosa's presidency came after the ANC's worst political moment, when Jacob Zuma, guilty of plundering the state coffers, led South Africa.

Since 2019 Ramaphosa has tried to fight extreme corruption, but the results have been very disappointing and opponents have repeatedly called for his impeachment, but without gaining a parliamentary majority. The ANC remains the strongest party, yet consensus may drop below the 50 per cent threshold. Ramaphosa won the primaries against his health minister and has said he is ready to lead South Africa for another term, but it remains to be seen how many citizens will go to the polls and, above all, whether the younger classes will want to express their dissent from a system of power that is now chronicled.

South Africa is also a leader at the international level and its membership of Brics - which since 2009 has grouped together the world's emerging economies (Brazil, Russia, India and China, joined by South Africa in 2010 and, from 1 January 2024, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates) - gives it a key role in the chessboard of the global South, especially in view of the opening of a geopolitical front stretching from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic Ocean.

The triple injustice against the Global South

Also expected at the polls are the citizens of Algeria and Tunisia, two countries with which, for historical and geographical reasons, Italy boasts long and complex relations. Algeria is led with an iron fist by President Abdelmajid Tebboune, a 78-year-old man who has centralised much of the power on himself. This is nothing new for the Algerian state, which has a long tradition of military and civilian rulers who have imposed robust control over the population. Tebboune is one of these: he inherited the country from Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who dominated the scene for a decade.

Tebboune, who prior to his presidency was a minister, acceded to the demands for the renewal of society and above all of the Hirak movement, the offspring of the Arab Springs, but with the passage of time he has been harsh in repressing all forms of dissent. In next December's elections he is the big favourite, but a massive abstention is expected, especially from the younger generation.

More interesting is the situation in Tunisia, where the chain of upheavals known as the Arab Springs began in 2011. In the country, the suicide of Mohamed Bouazizi - a young street vendor who set himself on fire in protest against rampant corruption - triggered the protests of an entire people, tired of seeing Ben Alitirirannare over Tunisians. The contagion had then reached the entire Arab world, dethroning Hosni Mubarak in Egypt and Muammar Gaddafi in Libya.

Today, however, the feeling is that Tunisia has been deeply disappointed by what the Springs seemed to bring to the Mediterranean. The first president of the new course, the doctor and activist Moncef Marzouki, was not rewarded by the voters who in 2014 chose Beji Ciab Essebsi, an 88-year-old man who had worked for a long time with Habib Bourguiba, the founder of modern Tunisia. Essebsi faced a deep economic crisis and a resurgence of international terrorism, dying six months before the end of his term.

With galloping inflation and a foreign debt that had become abnormal, in 2019 Tunisians elected Kais Saied, who had presented himself as an independent and innovator. A university professor and jurist, Saied focused on the fight against corruption, convincing the younger, educated classes to support him. In the summer of 2021, however, he first sacked the executive and then froze the Tunisian parliament, ruling by presidential decrees, centralising powers on himself and calling a referendum that was boycotted by the oppositions, just like the last parliamentary elections. In the run-up to the vote he remains the big favourite. Despite the fact that he wanted the arrest of journalists and opponents, he continues to have a large popular following.

Few seem able to stop the race for his re-election, perhaps only Olfa Hamdi, the leader of the Third Republic party who has announced her candidature. An energetic woman, a former Tunisair administrator. Then there are the Islamists of Ennadha, who should run with their own candidate, while the Ugtt, the great Tunisian trade union, perhaps at this moment the only solid opposition to Saied, could play a leading role.

La tua donazione ci servirà a mantenere il sito accessibile a tutti

Riformata. Così il governo vorrebbe la magistratura, ma l'obiettivo è solo limitarne il potere

La tua donazione ci servirà a mantenere il sito accessibile a tutti